| Communication team

Models and the transformation process - how do they fit together?

by Anke Möhring and Fatma Fevzi

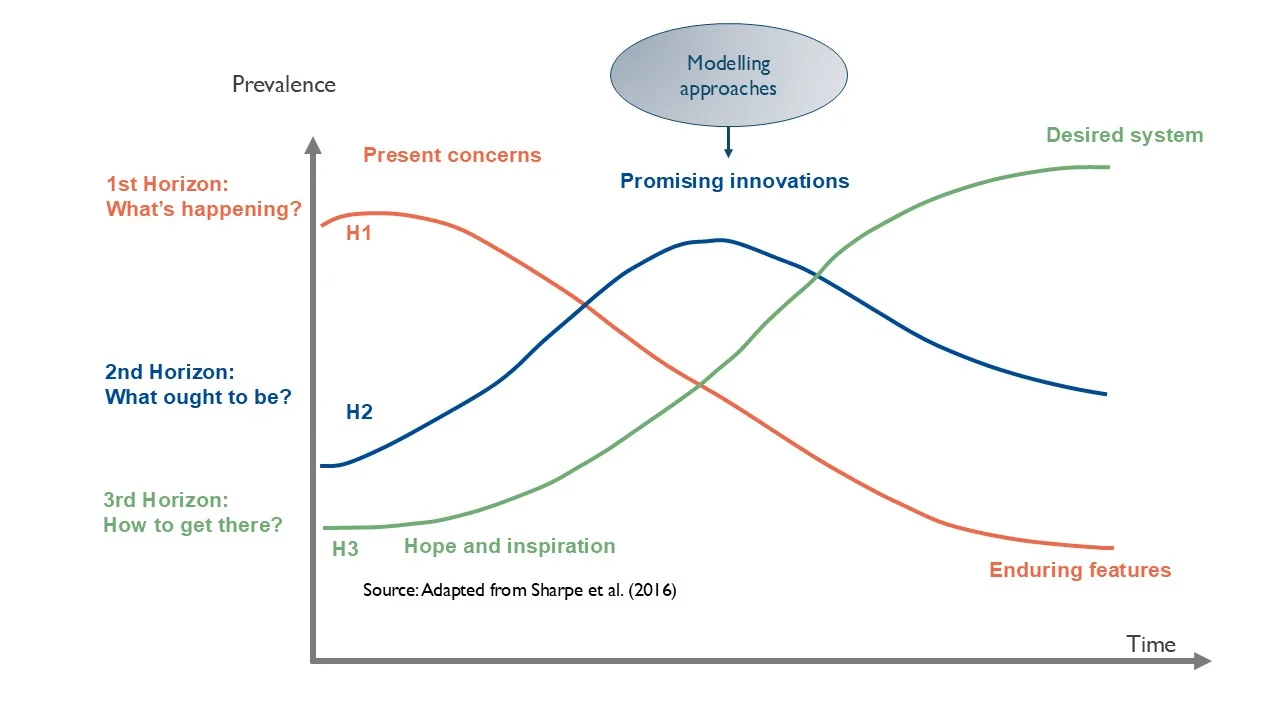

The trans4num project aims to identify pathways to nature-based solutions (NBS) in the field of circular nutrient management, with the broader ambition of contributing to the socio-ecological transformation of the existing agricultural system. However, this transformation process implies working with complexity (e.g. of the food system) and uncertainty (about the future), necessitating different tools to support the dialogue around the three horizons of transformative change[1]: the current system’s way of functioning, its challenges and opportunities (Horizon 1); the aspirational future that would emerge from transforming the current system (Horizon 3); and the transitional innovative activities and strategies that are promising in terms of achieving transformation (Horizon 2).

[1] For more information regarding the three-horizons approach, check out Sharpe et al. (2016) and Schaal et al. (2023).

The role of models within the transformation process envisaged by trans4num is versatile, but they are primarily embedded in the second stage of transformative change. They can help simulate how the transitional state might unfold with the innovations being introduced at each site (H2), and the effect of possible interventions, such as policies, incentives or infrastructure investment strategies, that support a shift towards circular nutrient management. trans4num models can thus support in navigating the transition stage, which requires a careful selection of innovations and interventions. Three models in trans4num contribute differently and together to this ambition:

- The Food System Model (FSM) explores the large-scale interactions between changes in production and consumption patterns, trade and input use, and their effect on the nutrient flows within the entire food system at the supra-regional and national level, and beyond.

Ø Therefore, the leading question of the FSM is: What would happen to the regional or national food system and its impacts if NBS innovations are applied on a larger scale?

- The Agent-Based Model (ABM) captures decision-making dynamics at the farm level, including the ways in which profitability, cooperation, and peer influence shape the adoption of NBS.

Ø The ABM can provide an ex-ante policy impact assessment based on the following question: To what extent can policy interventions accelerate the adoption of the NBS innovation and encourage more circular nutrient management in the region?

- The Decision Support Tool (DST) operates between field and regional scale and focuses on site-specific land-use interventions. The DST facilitates the dialogue between local stakeholders in searching for an optimal placement of NBS practices in space.

Ø It answers questions like: Where would the placement of an NBS practice be most effective for achieving environmental targets in a region? Or: Which trade-offs might occur as a result of the NBS placement?

Participatory model scenario development Modelling within the framework of projects like trans4num, which aim to contribute to a systemic transformation, requires a participatory approach, especially when deriving relevant model scenarios (see box 1 for scenario definition). This involves incorporating different types of knowledge: system knowledge (what are the dynamics of the current situation?); target knowledge (how should the better, more sustainable system look like?); and transformation knowledge (how can we get from the current system to the desired state?)[2]. The model scenario development process described below sits at the intersection of these types of knowledge: it builds upon the different backgrounds and knowledge provided by local stakeholders, project partners and modellers to simulate and test hypotheses about future circular nutrient management systems in different European contexts.

[2] More on the types of knowledge in this blog post or in (Lieberherr et al., 2025).

Box 1: What do we mean by scenarios? According to Lieberherr et al. (2025), scenarios are: “plausible and possible future pathways, which can be described through narratives and numerical representations. They provide meaningful and internally coherent alternatives to each other, enabling a comprehensive exploration of future possibilities. Drivers of change shape these potential future pathways... These drivers of change influence various context factors, which are the characteristics of a specific place that can impact the system's ability to undergo transformation.”

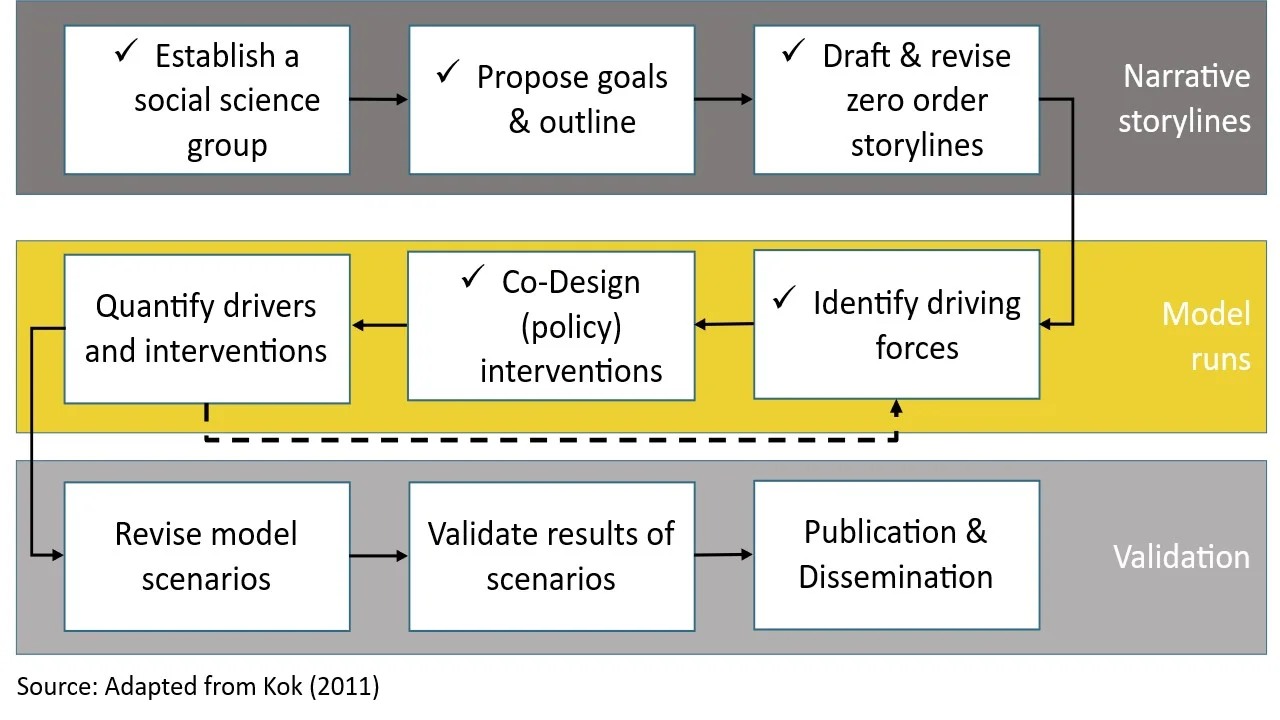

For modellers, scenario development starts with narratives which build the basis for simulation and analysis. Those narratives can be assumptions of stakeholders about the plausible future of the socio-ecological system – not only capturing the innovation but also the socio-economic and political developments. Taking the example of the ABM, we describe below how a participatory approach can enhance the three modelling approaches in trans4num and contribute to the bottom-up design of transformation pathways.

Co-design of policy interventions for the agent-based model

The starting point for the scenario development process in the ABM were the NBS-site-specific storylines proposed by local stakeholders and project partners. The NBS-site storylines included both the current situation and the challenges of the transition towards the envisioned future along with opportunities and barriers that could enable or block the transformation. They also referred to agents in the system as main characters that would need to be addressed via future interventions. Based on these narrative storylines, we derived driving forces, such as key assumptions about crop choices, environmental pressures, farmer cooperation, which served as a basis for the brainstorming session at the trans4num General Assembly in Denmark on how to co-design intervention strategies with stakeholders.

Despite the differences between the NBS-sites, three common driving forces behind (non-) adoption of NBS practices became prominent from the NBS-site storylines:

- the conditions of the existing eco-schemes;

- the cost of (non-)adoption and economic risk;

- access to advisory services and farmers’ network.

We then guided the intervention co-design process for each NBS-site with the following questions:

- What kind of political, social or economic interventions would you propose to address one or multiple of the listed drivers of NBS (non-)adoption?

- What would be the aim or target of the intervention?

- Which aspect of the NBS-site innovation does the intervention refer to?

- How can the intervention be implemented? What are opportunities and barriers of its implementation?

Important was that each intervention addressed one or multiple drivers directly and its target was defined explicitly. We, therefore, reminded participants that these interventions will be translated into model scenario parameters, which implies that any detailed information about their target and the system aspect they refer to is very valuable.

Lastly, we also discussed the framework and its applicability to a larger group of stakeholders at NBS-sites, using the breakout session as a space to think about both the future stakeholder engagement events and the potential of the NBS innovations for a regional-scale transformation.

Preliminary results from the breakout sessions

The discussions resulted in 3-4 possible interventions identified per NBS-site. Imagining plausible futures and explicit intervention strategies without a larger group of stakeholders and experts, however, seemed challenging. Moving from abstract concepts of socio-economic and political tensions to concrete, context-sensitive strategies required more time and effort than expected. Nevertheless, we could identify common patterns between strategies at different sites that can be validated with stakeholders as part of the next events and guide the discussion around the question of how to upscale the site-specific NBS innovations to the regional or even national level.

The following list emerged as an outcome of the brainstorming session:

Adjusting the current European eco-schemes for agricultural nutrient management with regards to the conditionality (e.g. voluntary vs mandatory requirements), the indicators, the payments levels and the eligible practices. Project partners also emphasized the importance of improving coherence across policy frameworks that are aimed at nutrient use in agriculture, especially between the Water Framework Directive and the CAP Agri-Environment measures.

Market-based interventions like certification or labelling schemes for products from farms using NBS practices to reward farmers for their efforts. To reduce the financial risks of adopting such practices, partners suggested options like top-up payments for these products. Conversely, they proposed stricter regulatory measures such as nutrient quotas or fertiliser taxes for farms that do not transition towards more sustainable nutrient management.

Supporting advisory services to help farmers transition. This includes addressing current knowledge gaps and transforming advisory business models, which are often still aligned with conventional agricultural systems and may lack incentives to promote innovative

Outlook

The next step in the participatory scenario development process is to validate the proposed interventions with a wider audience of stakeholders. Working together with project partners responsible for stakeholder engagement events, we will be able to communicate the suggested interventions to local stakeholders and collect further input regarding their plausibility. For the modellers, however, the scenario development endeavour does not end there – we will also need to define the quantitative values of each driver for the baseline scenario (Business-as-Usual) and adjust the level of intervention in each scenario according to the proposed strategies. Finally, the quantified scenarios will be additionally validated with stakeholders at the NBS-sites to ensure their relevance before proceeding with dissemination.

References:

- Lieberherr, E., Dölker, J., Salomon, H., Schick, V., Logar, I., Bugmann, H., ... & Hoffmann, S. (2025). Science integration and a participatory scenario process. An inter-and transdisciplinary study from the Alps. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 34(1), 35-41.

- Schaal, T., Mitchell, M., Scheele, B.C. et al. “Using the three horizons approach to explore pathways towards positive futures for agricultural landscapes with rich biodiversity”. Sustain Sci 18, 1271–1289 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01275-z

- Sharpe, Bill, et al. “Three Horizons: A Pathways Practice for Transformation.” Ecology and Society, vol. 21, no. 2, 2016. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26270405 . Accessed 9 June 2025.

- “Three types of knowledge. (2025, April 30). Integration and Implementation Insights”. https://i2insights.org/2021/02/11/three-types-of-knowledge/